The 2022 GESIS Klingemann Prize for the Best CSES Scholarship was awarded to Vicente Valentim for his article “Parliamentary Representation and the Normalization of Radical Right Support” in Comparative Political Studies. We are grateful that he has provided the following written summary and video presentation about his award-winning research.

Parliamentary Representation and the Normalization of Radical Right Support

by Vicente Valentim

Democracy is more than just a set of legal rules. Well working democracies should also promote a culture of tolerance and inclusion of diverse social groups. Such tolerance and inclusion, however, cannot fully rest on legal enforcement, as it should exist in realms where legal enforcement is not doable or desirable. For these reasons, a democratic culture relies on social norms that define boundaries of what is acceptable and desirable in a democracy. But what are these boundaries? How do they change over time? And can the success of new political actors normalize what was previously unacceptable?

These are some of the questions I tackle in my paper. I focus on how the success of radical-right politicians and candidates can normalize radical-right views. From peripheral political groups, radical-right politicians and parties have grown to become central to the policymaking process in many countries. One feature of this party family is their disregard of established social norms like those against the derogatory treatment of minority groups.

Following multidisciplinary literature on social norms, I assume that voters with radical-right views have an incentive to hide those views. Since the rhetoric and policy positions of radical-right parties defies established social norms, support for them can come at the cost of social sanctions. For example, their supporters may fear being judged or called out because of their views. In an effort to avoid such sanctions, they are likely not to publicly say what they think in private—a phenomenon often called preference falsification.

I argue that their success can make radical-right individuals more comfortable publicly expressing their private views. Being part of the legislative body of the country is a signal of acceptance that can make voters perceive social norms against the expression of radical right support as being weaker.

The difficulty with testing this argument empirically is that one cannot know what an individual’s true preferences are if they are consciously concealing them. Ideally, one would like to compare what individuals think in private to what they do in public; and check whether the gap between the two is reduced after the radical right is in parliament.

I overcome this problem with three complementary studies. The similarity across them is that they all find ways of comparing the preferences that individuals report in private and in public. The common logic is that the more private a given behavior is, the more likely someone is to act according to their private preferences. Conversely, the more public the behavior, the more likely one is to act in ways that follow social norms—even if that means deviating from what they think in private. As such, a comparison of the two provides a measure of how strong social norms for or against a given behavior are. The stronger the social norm is, the more likely it is that individuals will publicly deviate from what they privately think.

Following this logic, the first study proposes an observational measure for how publicly acceptable it is to support a given party. This measure is called reported vote. It captures the proportion of the official vote for a given party that is reported in post-electoral surveys. The logic is that, because voting is private, social pressures are not likely to influence it as much. As such, the vote share for a given party can be taken as a measure of how many individuals support that party in conditions of weak social pressure. In turn, the vote share for the same party as reported in surveys can be taken as a measure of how many individuals are willing to tell someone else (the survey interviewer) that they support it, in conditions of pressure to report the socially desirable answer. Finally, the proportion of the two can be taken as a measure of how much individuals perceive that it is socially acceptable to support a given party.

I start with showing that the radical-right is the only party family for which the official vote is under-reported in surveys. On average, for each five individuals that vote for a radical-right party, only four admit that support in a survey interview. This is not the case with parties of other ideologies.

Then, I assess whether the parliamentary representation of the radical right makes its supporters right feel more comfortable acting on that support. If my argument is correct, we should observe that, when the radical-right is in parliament, the share of the official vote for the radical right that is reported in surveys increases. This would suggest that, holding constant how many individuals support these parties, there are more individuals who feel comfortable admitting that support.

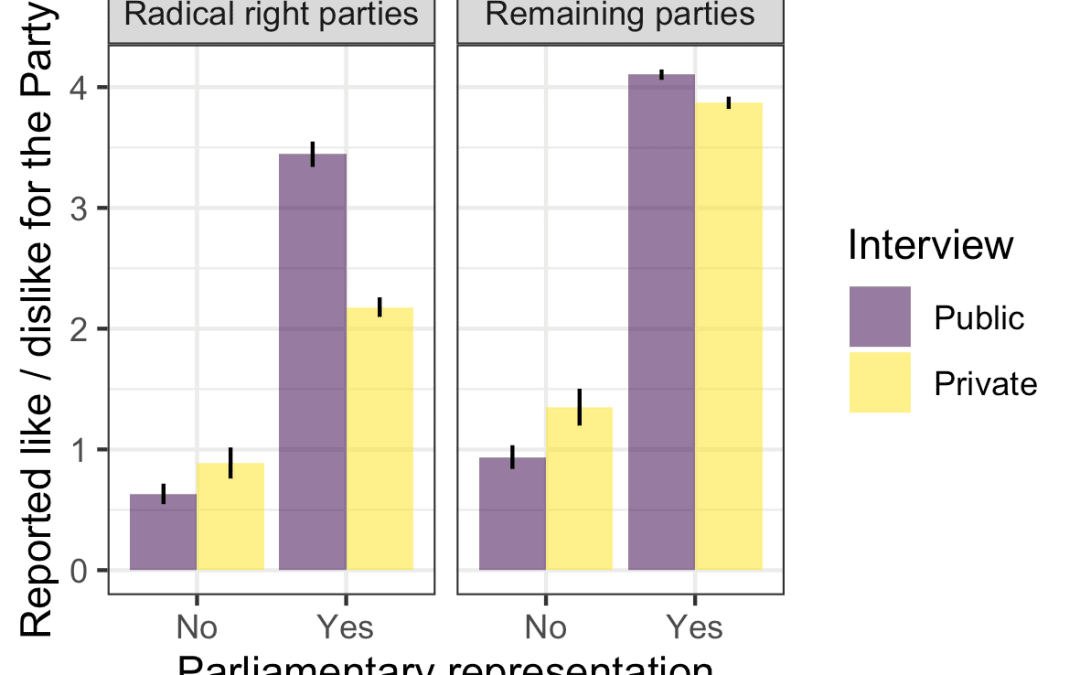

To test this expectation, I run a regression discontinuity design that takes advantage of exogenous variation induced by legally fixed thresholds to parliamentary representation. A graphical representation of these analyses is shown in Figure 1 below. The x-axis represents how many percentage points away from the electoral threshold (above or below) each radical right party was. The y-axis represents the proportion of the official vote for that party that was reported in post electoral surveys.

The figure shows that there is a jump around the electoral threshold (dashed vertical line in the plot). This means that when radical-right parties narrowly enter parliament, they are less under-reported in surveys than when they narrowly fail to enter parliament. This suggests that the parliamentary representation of the radical right does make individuals more comfortable showing support for them. The analyses suggest that, for each ten individuals that voted for a radical-right party, four to five more (depending on model specification) were willing to tell the interviewer that they did so if the party marginally entered parliament than if it narrowly failed to do so.

The shortcoming with these analyses is that, while the argument of the paper takes place at the individual level, the unit of analyses here is the party. To test whether the results hold at the individual level, Study 2 finds a way of approximating the analyses at that level.

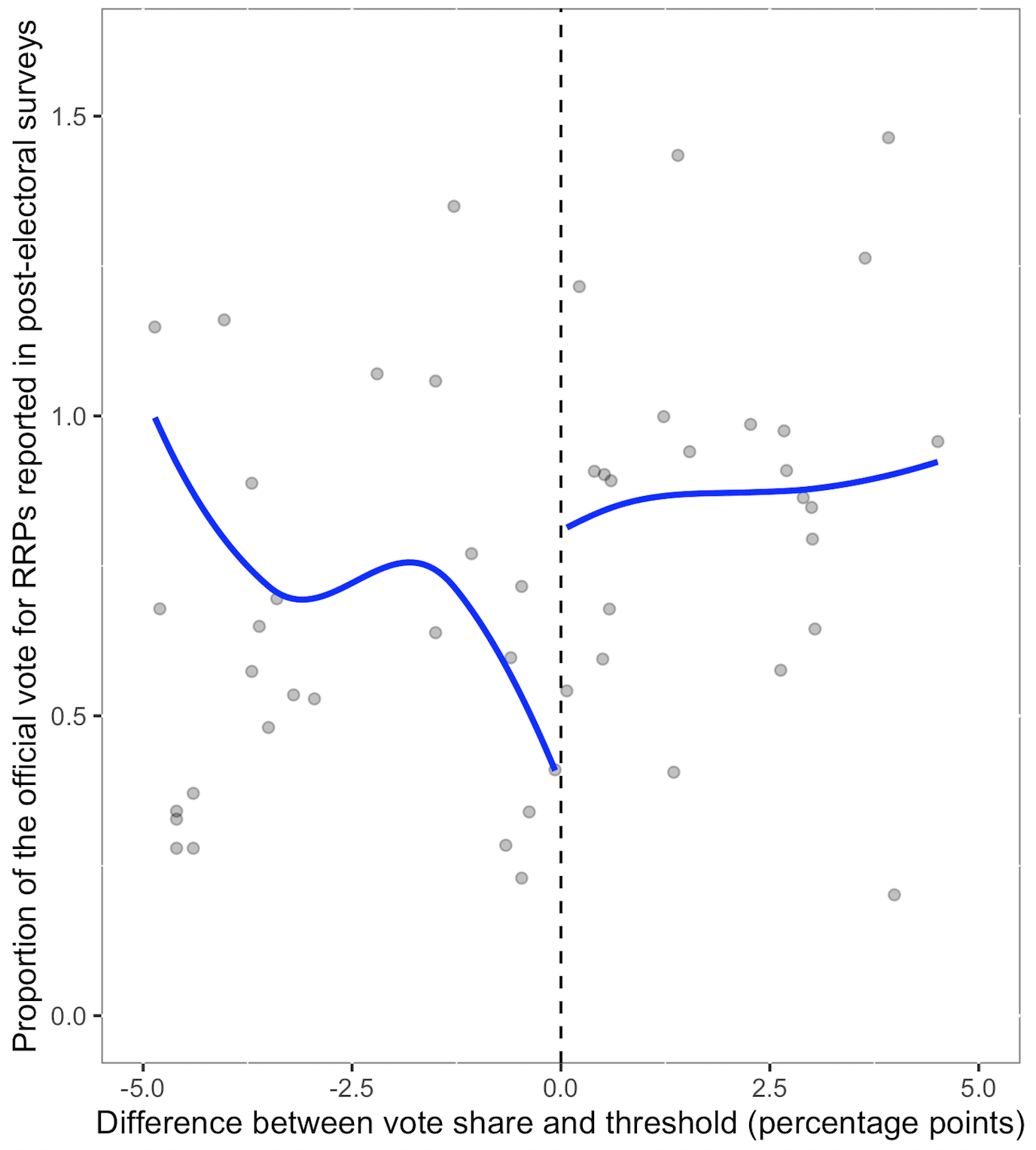

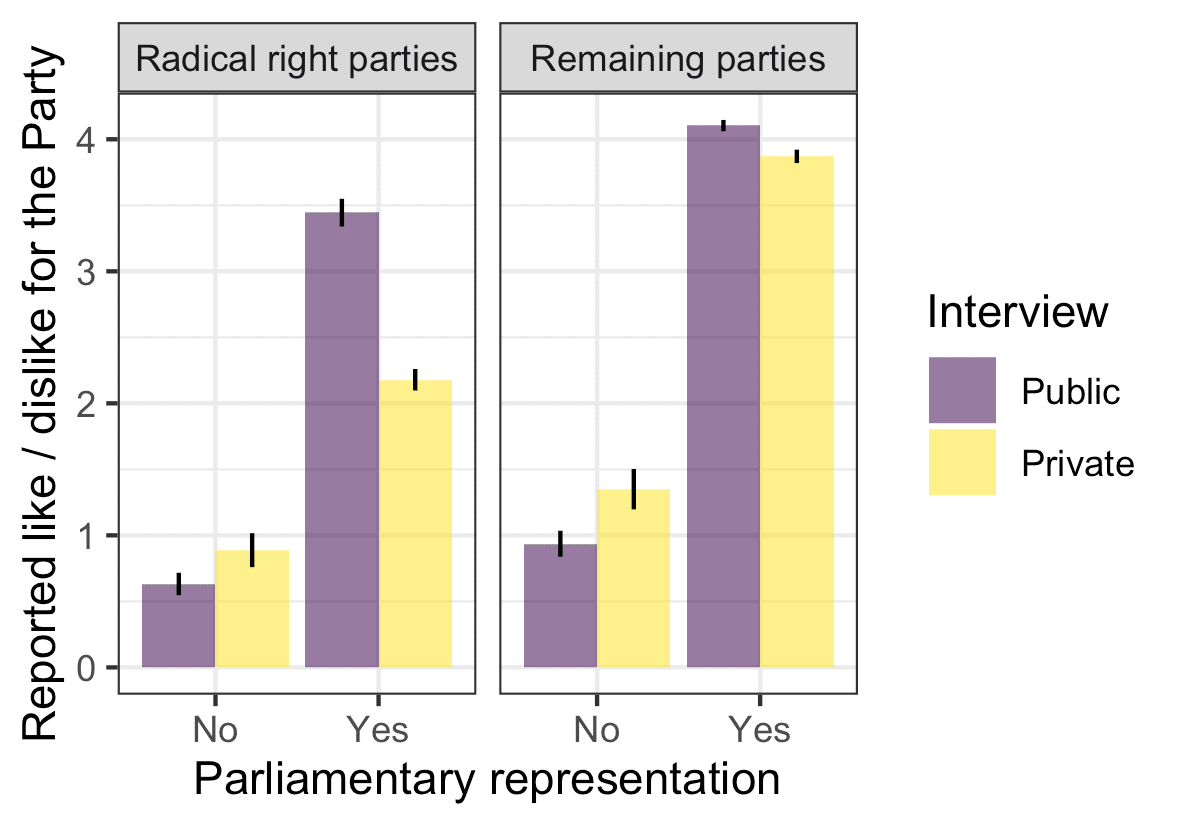

To do so, I look into some post-electoral surveys included in the CSES that use different interview modes on different respondents. Some were interviewed in ways that kept their answers private (like mail back and internet modes); while others had to convey their answer to an interviewer (like face to face and telephone interviews).

This difference in interview modes generates variation in the level of pressure not to report radical right support. I assume that respondents interviewed in more are more likely to reveal their private preferences. Then, I regress a variable that asks respondents how much they like each party on each respondent’s interview mode (private or public), whether the party is radical right or not, whether the party is in parliament or not, and the two-way and three-way interactions between these variables.

These analyses, shown in Figure 2, suggest that individuals report to like radical right parties less than the remaining parties; to like parties which are in parliament more; and they report to like parties more when the mode of interview is private. But the difference between how much individuals report liking a party in private and public modes of interview is reduced when the party makes it to the parliament, and this reduction is larger in the case of radical right parties. This pays further empirical support to the normalization effect of parliamentary entry.

These two complimentary studies still leave one element of the argument untested. The argument is dynamic: it contends that the same party will be stigmatized before it enters parliament but, if it does enter parliament, it will become normalized. Since both the party-level analyses and the individual-level analyses are rather static, they cannot test for this element of the argument.

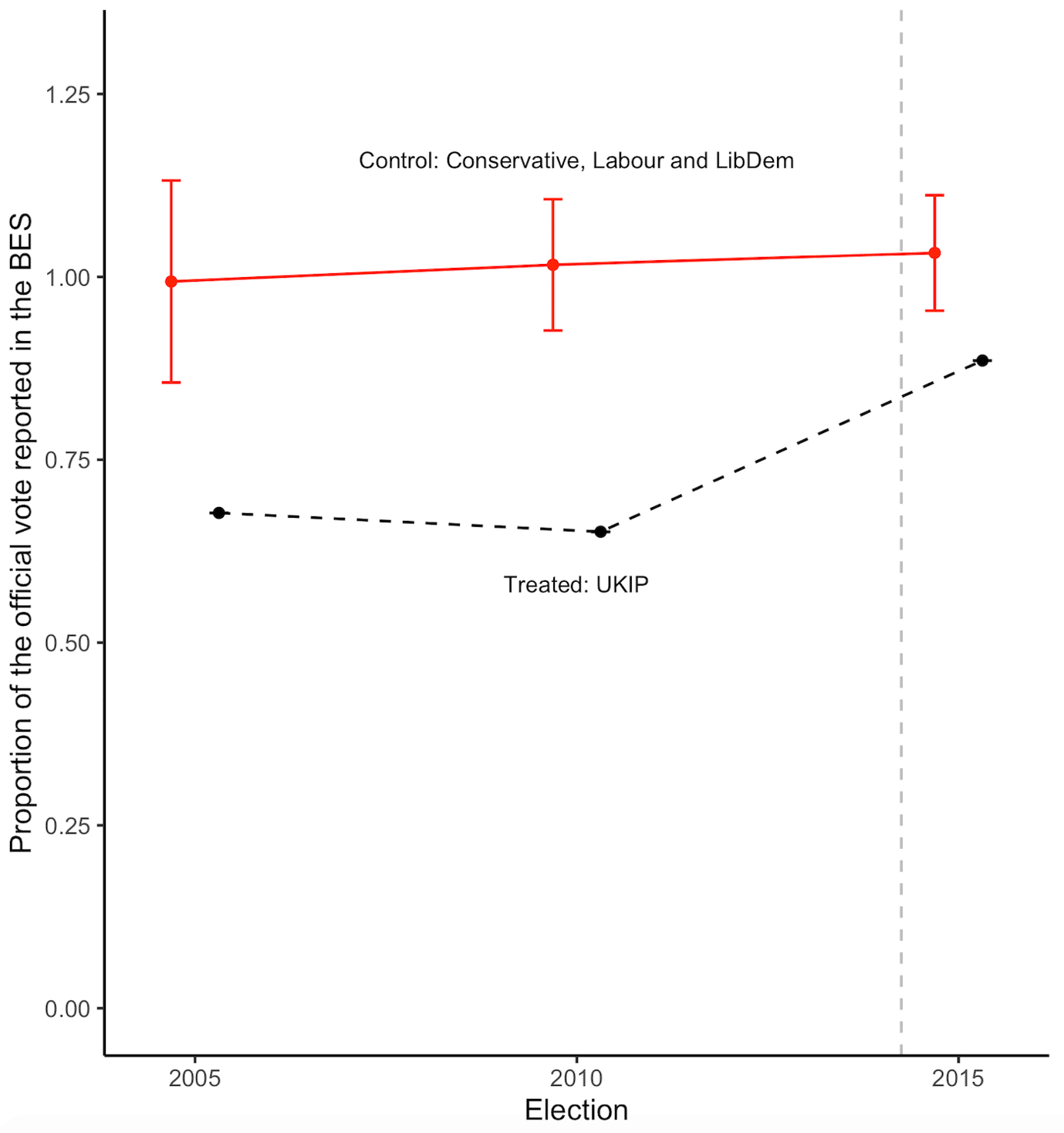

To overcome this shortcoming, in Study 3 I look into the case of one radical right party that ran for several elections before making it to parliament: the UK independence party. I use the same dependent variable as in the aggregate analyses of Study 1—reported vote, which captures the proportion of the official vote for the party that is reported in post-electoral surveys. Then, I run difference-in-differences models that compare the evolution of this variable for UKIP to that of the mainstream parties in the country.

The results, shown in Figure 3, again suggest that the vote share for UKIP was significantly less underreported after it made it to parliament in 2015. For each ten individuals that voted for the party, two more were willing to tell the interviewer that they had done so after the party entered parliament.

What can we conclude from these analyses? A body of literature has argued that in democracies, there tend to exist social norms against the expression of views that are at odds with liberal democracy. These results suggest, however, that these norms were what theorist Temi Ogunye calls fragile norms. Many individuals abided by them but did not truly change their private preferences. For this reason, information updates like election results can make individuals suddenly feel comfortable publicly revealing what they already thought in private.

More broadly, the paper suggests that individuals can often change their behavior even if their preferences remain constant. Individuals survey their social environment looking for cues of what is socially acceptable. Those cues can make them more or less likely to act on the preferences they hold in private—even if those preferences themselves do not change.