The 2019 GESIS Klingemann Prize for the Best CSES Scholarship was awarded to Ruth Dassonneville of the University of Montreal and Ian McAllister of the Australian National University for their article “Gender, Political Knowledge, and Descriptive Representation: The Impact of Long-Term Socialization” in the American Journal of Political Science.

The authors received their prize and presented their work during a reception at the 2019 Annual Meeting of the American Political Science Association (APSA) in Washington DC, United States. We are grateful that they have provided the following summary of their award-winning research.

By Ruth Dassonneville and Ian McAllister

Political knowledge is considered one of the most important resources for citizens in electoral democracies. Citizens that are more knowledgeable not only participate more, they also cast votes that better reflect their preferences and interests. Women, however, are consistently found to have levels of political knowledge that fall short of those of men.

Given the important role of political knowledge, the existence of a long-standing gender gap in political knowledge has spurred many studies aiming to explain why women’s levels of political knowledge are consistently lower than those of men. This literature has linked women’s lower levels of knowledge to their human capital and their exposure to political information. Others have argued that the gender gap in political knowledge reflects the characteristics of the surveys and the questions that are used to measure political knowledge. Even when taking all these factors into account, however, a gender gap in political knowledge remains – and it proves stable over time and space.

In the face of this consistent and stable gap between men’s and women’s levels of political knowledge, scholars have recently started to draw attention to the role model function of elected politicians in explaining citizens’ political engagement, interest, and knowledge. In short, the argument is that as the share of women elected representatives increases, women will become more politically engaged, and as a consequence, more knowledgeable. While this is a compelling argument, the results of the research that has tested the connection between women’s descriptive representation and the gender gap in political knowledge are mixed.

In our paper, we argue that previous studies have failed to find strong evidence of a link between women’s descriptive representation and the gender gap in political knowledge because it has – implicitly – assumed that the effects will be direct and immediate. That is, it has assumed that an increase in the number of elected female politicians will immediately boost women’s political engagement and knowledge. This assumption is unlikely to hold, we argue, because political attitudes and knowledge are stable individual traits. From work in the field of political socialization, for example, we know that political attitudes develop in childhood and adolescence, and remain largely stable in adulthood. As a result, political change mostly occurs through a process of generational replacement.

Applying these insights to explaining the gender gap in political knowledge, our expectation is that women’s descriptive representation is important, but that its impact will be evident only in the long-term, through the imprint it leaves on citizens’ political attitudes. More precisely, we hypothesize that female respondents who entered the electorate at a time when more women were represented in politics will have similar levels of political knowledge when compared to men.

To test our hypothesis, we use the individual-level data from the first three modules of the Comparative Study of Electoral Systems (CSES) and the 2009 European Election Study (EES). Both datasets include a series of items to capture respondents’ levels of political knowledge. We are mostly interested in knowing whether women’s descriptive representation moderates the effect of gender on political knowledge. Therefore, we add to the datasets indicators of women’s descriptive representation. In line with previous research, we focus on the percentage of women elected representatives (in the lower house). We constructed a short-term indicator that captures the percentage of women elected representatives at the time of the survey year, as well as a ‘long-term’ indicator that captures the percentage of women elected representatives at the time the respondent entered the electorate (we proxy this by taking the average percentage of women in a respondent’s country when the respondent was between 18 and 21 years old).

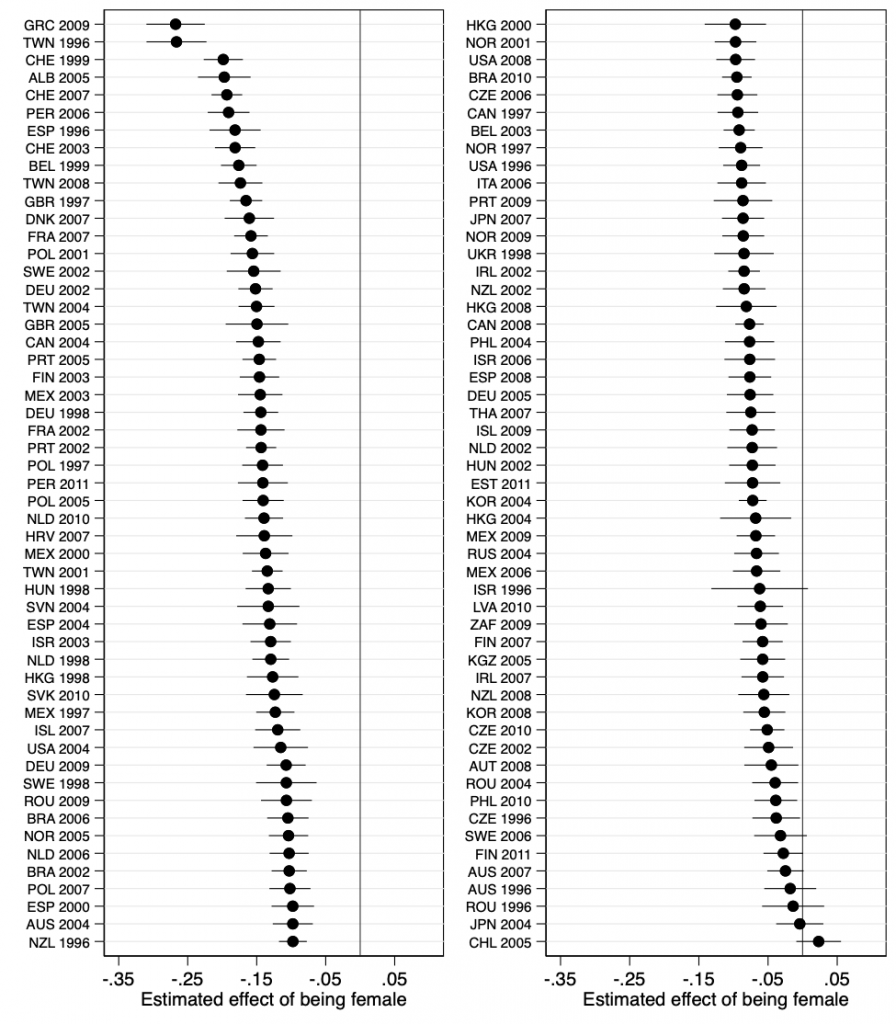

We focus here on the results from our analyses of the CSES data, but results are consistent regardless of whether we use the CSES or the EES datasets. First, in terms of the gender gap in political knowledge, our analysis of the CSES data show a picture that is very consistent with earlier work. As can be seen in Figure 1, across countries and across time, we find strong and quite consistent evidence of women scoring less well on political knowledge.

Figure 1. The estimated gender gap in political knowledge

Note: Estimates are regression coefficients and 95% confidence intervals of the effect of being female (vs. male) on a 0-1 sum scale of political knowledge. Source: CSES Modules 1, 2, and 3.

Are these gender-differences in political knowledge correlated with women’s descriptive representation? To verify this, we estimated a series of multilevel models, in which we added controls for individual-level predictors of political knowledge (e.g., age and level of education), indicators of the survey modes and the type of questions that were relied on to measure knowledge, as well as contextual level variables that are likely correlated with political knowledge (e.g., level of democracy and economic conditions). Our interest, however, is in the interaction between respondents’ gender, and our short- and long-term indicators of women’s descriptive representation.

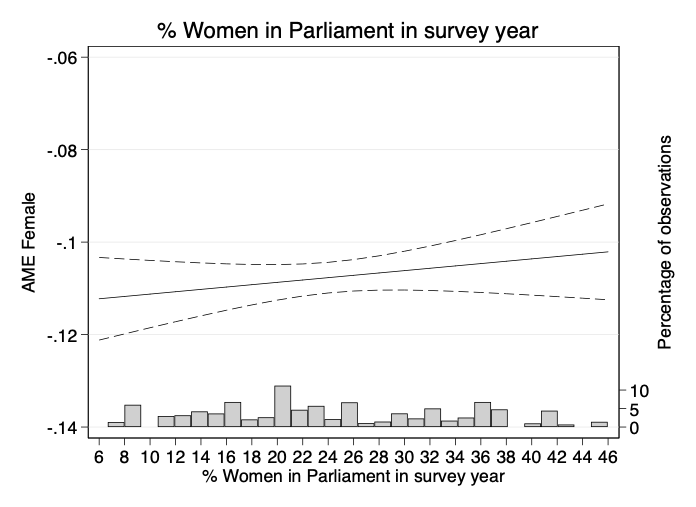

Figure 2 presents the results for a traditional, short-term, measure of women’s descriptive representation. It shows that the average marginal effect of being female (vs. male) on political knowledge, at different levels of the percentage of women elected in parliament at the time of the survey. Figure 2 shows there is virtually no effect of descriptive representation at the time of the survey on the gender gap in knowledge. Women are consistently estimated to have a political knowledge score that is about .11 points lower than that of men, regardless of how many women are elected in parliament.

Figure 2. The effect of the percentage of women in parliament on the gender gap, short-term effect

Note: Average marginal effect of being female (vs. male) on political knowledge (measured on a scale from 0 to 1) by women’s representation at the time of the survey. Dashed lines indicate 95% confidence intervals. Histogram summarizes the distribution of the moderating variable.

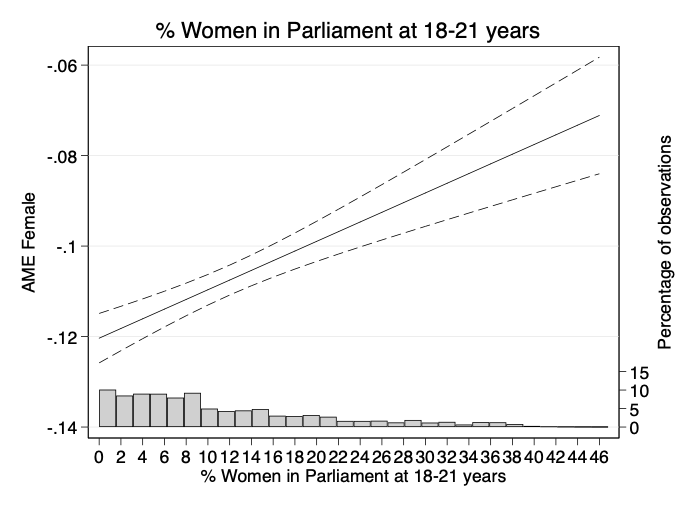

When turning to the long-term indicator of women’s representation, however, the picture changes. As can be seen from Figure 3, the percent of women that was elected in parliament when a respondent entered the electorate correlates significantly with the size of the gender gap in political knowledge. The effect is also sizeable. The knowledge gap between a man and a woman who entered the electorate at a time when no women held seats in their national parliament is estimated to be about -.12. For those entering the electorate at a time when about 20% of the representatives were women, the gender gap is -.09 and it is further reduced to about -.07 for those entering the electorate when female representation was 40%.

Figure 3. The effect of the percentage of women in parliament on the gender gap, long-term effect

Note: Average marginal effect of being female (vs. male) on political knowledge (measured on a scale from 0 to 1) by women’s representation when a respondent was 18-21 years old. Dashed lines indicate 95% confidence intervals. Histogram summarizes the distribution of the moderating variable.

These results support our theoretical argument, that women’s descriptive representation matters and is correlated with a decreased gender gap in political knowledge – but only through the imprint it leaves on individuals in the long-term. However, are these effects in line with the theoretical arguments that stress the symbolic importance and role model effects of female representatives on female citizens?

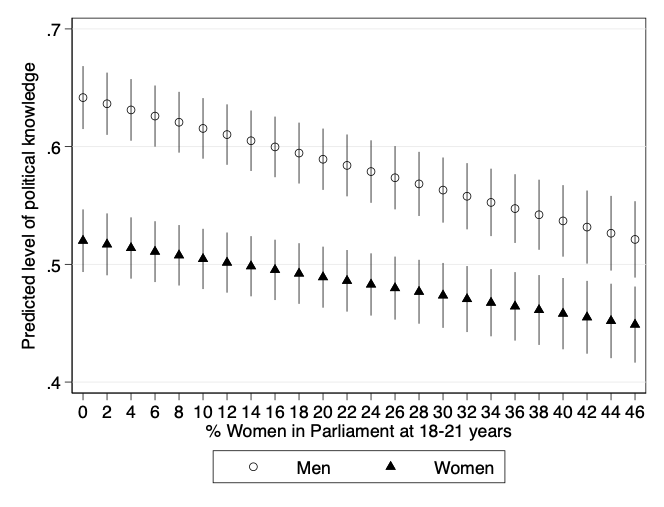

To gain insights into this question, Figure 4 shows the predicted levels of political knowledge among men and women. These results show that while women’s levels of political knowledge seem to be largely unchanged, men’s knowledge levels are lower as the percentage of women in parliament – during their formative years – increases. Our correlational data do not provide any insights into the reasons for this decline in men’s knowledge levels as the descriptive representation of women increases. Whatever the explanation, it is clear that more research is needed into the mechanisms that lead the gender knowledge gap to decrease as women are better represented in politics. Our results suggest that such work should not only focus on the effects among women, but also those among men.

Figure 4. The effect of the percentage of women in parliament on men’s and women’s level of political knowledge

Note: Predicted level of political knowledge (measured on a scale from 0 to 1) by women’s representation when a respondent was 18-21 years old among men and women. Spikes indicate 95% confidence intervals.