The 2018 GESIS Klingemann Prize for the Best CSES Scholarship was awarded to André Blais of the Université de Montréal, Eric Guntermann of the Université de Montréal and University of California Berkeley, and Marc André Bodet of the Université Laval for their article "Linking Party Preferences and the Composition of Government: A New Standard for Evaluating the Performance of Electoral Democracy" that was published in Political Science Research and Methods in 2017. The authors received their prize and presented their work during a reception at the 2018 Annual Meeting of the American Political Science Association (APSA) in Boston, United States. We are grateful that they have provided the following summary of their award-inning research.

Linking Party Preferences and the Composition of Government: A New Standard for Evaluating the Performance of Electoral Democracy

The goal

Elections are supposed to enhance the link between citizens’ preferences and the composition of government. Proportional representation (PR) has traditionally been assumed to strengthen that link since it allows a fair transformation of vote shares into seat shares in parliament. That assumption has been challenged in previous research (Blais and Bodet 2006; Golder and Stramski 2010) which shows that PR elections do not produce greater congruence between citizens’ and governments’ ideological orientations. We argue that elections are not only about ideology; they are first and foremost about which parties will govern. We therefore propose a new and original standard for evaluating the performance of electoral democracies: the degree of correspondence between citizens’ party preferences and the party composition of the cabinet. That standard is based on the simple (and reasonable) assumption that democracy works better when people are governed by parties that they like and not by parties they dislike.

We propose three specific criteria for assessing the correspondence between citizens’ party preferences and the party composition of the cabinet:

- The proportion of citizens whose most preferred party is in government

- Whether the party that is most liked overall is in government

- How much more positively governing parties are rated than non-governing parties

The data

We use CSES data that include a party like/dislike question in which respondents are asked to rate each party on a 0-10 scale.

We focus on lower house elections in non-presidential democracies. Our sample includes 87 legislative elections held in 35 countries. We distinguish elections held under PR and under non-PR and on the basis of disproportionality between vote and seat shares. For each party, we compare its ratings in the electorate and the proportion of seats it had in the cabinet that was formed after the election.

Results

Criterion 1: How many citizens have their preferred party in government?

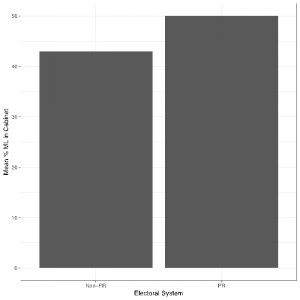

More people have their preferred party in government under PR, and this is due to the fact that PR leads to the presence of more parties in the cabinet. As is shown in Figure 1, 50% of citizens, on average, get their most liked party in government under PR, compared with 43% in non-PR elections. On this first criterion, PR elections perform better.

Figure 1: Average percentage of citizens whose preferred party is in government by electoral system

Criterion 2: Is the most liked party in government?

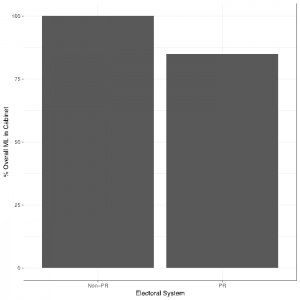

We compute the mean ratings of all the parties in each election to identify the party that is most liked overall and determine whether that party is in government or not. The most liked party was in government after each of the ten non-PR elections, while that was not always the case following PR elections. Namely, in 11 PR elections out of 74 (15%), the most liked party found itself in the opposition. On this second criterion PR elections perform worse.

Figure 2: Percentage of elections in which the overall preferred party is in government by electoral system

Criterion 3: Are governing parties better liked than non-governing parties?

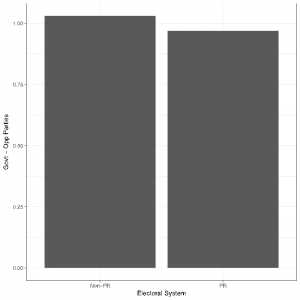

Governing parties are better liked than opposition parties in 82 of the 87 elections. But the mean differential, as can be seen in Figure 3, is slightly more positive in non-PR elections. This is so because PR elections usually lead to the formation of coalition governments that often include at least one small party, and small parties are usually less liked than large parties. On this third criterion PR elections also perform worse

Figure 3: Average difference between weighted ratings of parties in government and opposition

Conclusion

We propose a new perspective for evaluating the performance of electoral democracies that focuses on the link between citizens’ party preferences and the composition of government. Simply put, democracy performs better when governing parties are better liked than non-governing parties since people prefer to be governed by parties that they like. We propose three specific criteria for assessing that correspondence. We find that PR elections perform better on one criterion and worse on the other two. In short, before concluding that one system is better than the other we must decide which aspects of citizens’ preferences matter the most.

For more details, see André Blais, Eric Guntermann, and Marc André Bodet (2017). “Linking Party Preferences and the Composition of Government: A New Standard for Evaluating the Performance of Electoral Democracy.” Political Science Research and Methods 5(2): 315-331.