The 2016 GESIS Klingemann Prize for the Best Scholarship using CSES data was awarded to Kimuli Kasara of Columbia University and Pavithra Suryanarayan of Johns Hopkins University for their paper "When do the rich vote less than the poor and why? Explaining turnout inequality across the world" that was published in the American Journal of Political Science in 2015. The authors received the prize and presented their work during a reception at the annual meeting of the American Political Science Association (APSA) in Philadelphia, USA on September 2, 2016. They kindly contributed the following synopsis of their work.

When do the Rich Vote Less than the Poor and Why?

Explaining Turnout Inequality Across the World

Kimuli Kasara and Pavithra Suryanarayan

Arendht Liphart observed that “voter turnout is an excellent indicator of democratic quality” in part because he believed that the poor and socially marginal were less likely to vote (Lijphart 1999). Lower rates of electoral participation by the economically disadvantaged, while being normatively undesirable in a democracy, also have implications for the types of parties that win elections and the policies politicians will implement once in office. For these reasons, turnout inequality has been central to the study of both political behavior and political economy. For instance, the idea that the poor participate less has been used to explain why we might not observe an expansion in redistribution after democratization as canonical political economy models predict.

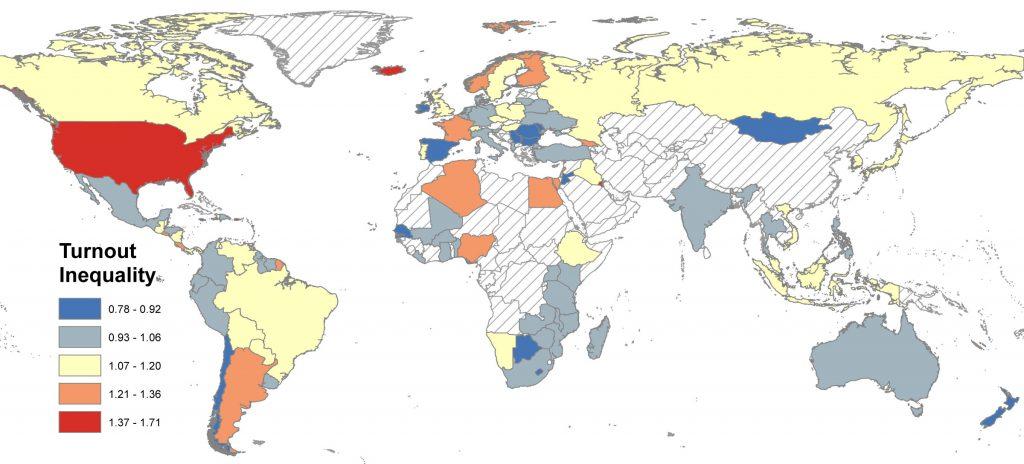

Most early research on socio-economic status (SES) and voting focused on voting behavior in advanced industrialized countries where it is often the case that the wealthy vote at higher rates than the poor. Our research began with the observation that income and turnout are often negatively correlated in the contexts we study – South Asia and sub-Saharan Africa. This “inverse” relationship between SES and voting has been documented in isolated studies in both regions as well as in Eastern Europe. Our paper, “When Do the Rich Vote Less Than the Poor and Why?: Explaining Turnout Inequality across the World (American Journal of Political Science, 2015), is the first to systematically document that “inverse” turnout inequality is not rare using data on 76 countries from the Comparative Study of Electoral Systems (CSES) and other survey sources. This figure from our paper, which maps the ratio of turnout rates of the wealthiest 20% in a country to turnout of the poorest 20%, shows variation in the relationship between wealth and turnout.

Figure 1: Turnout Inequality across the World

We offer an explanation for why income positively correlates with voting in some places and not in others. Our theory begins with a simple question – under what conditions will the relatively wealthy not vote, allowing the votes of the poor to be decisive in setting public policy? Modern democracies vary considerably in the degree to which states have the capacity to tax the wealthy even when voters demand it. We argue that income will positively correlate with voting when the potential tax exposure of the rich is high. Our argument involves the incentives of both wealthy citizens and vote-seeking politicians. Where the state can tax the wealthy, relatively rich voters have a greater incentive to participate in politics and politicians are more likely to use fiscal policy to appeal to voters.

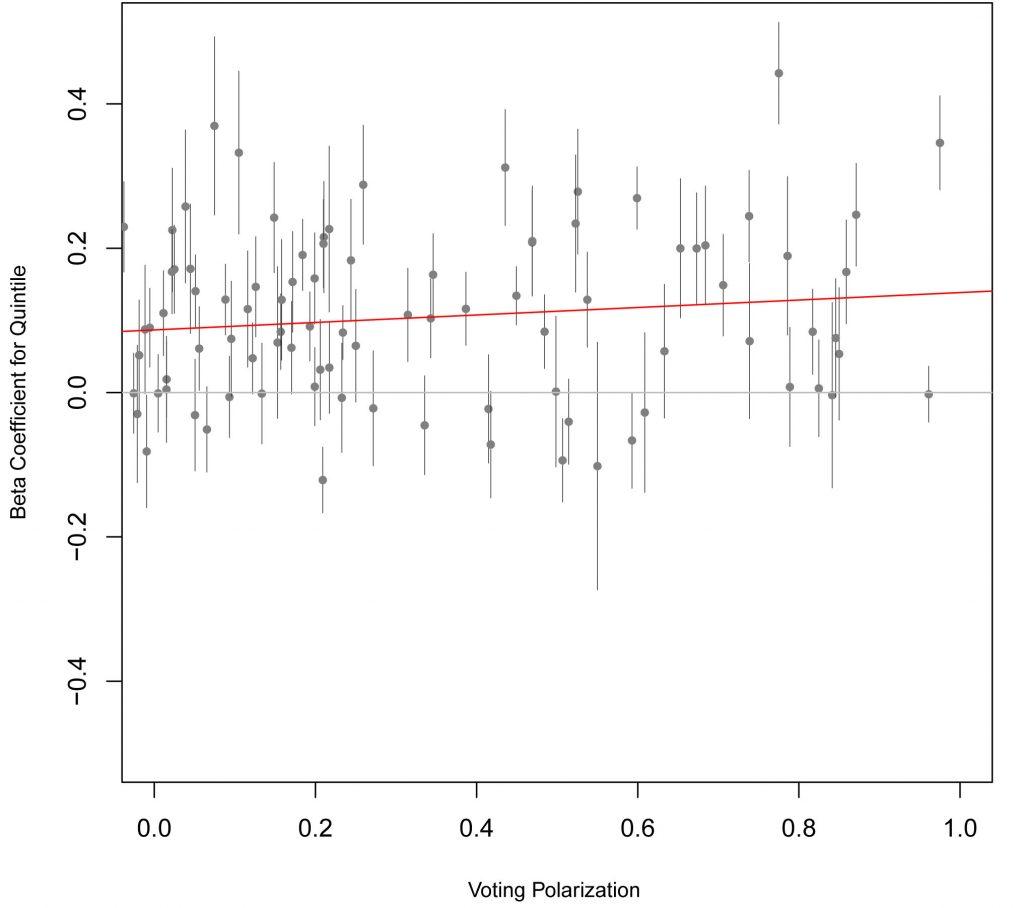

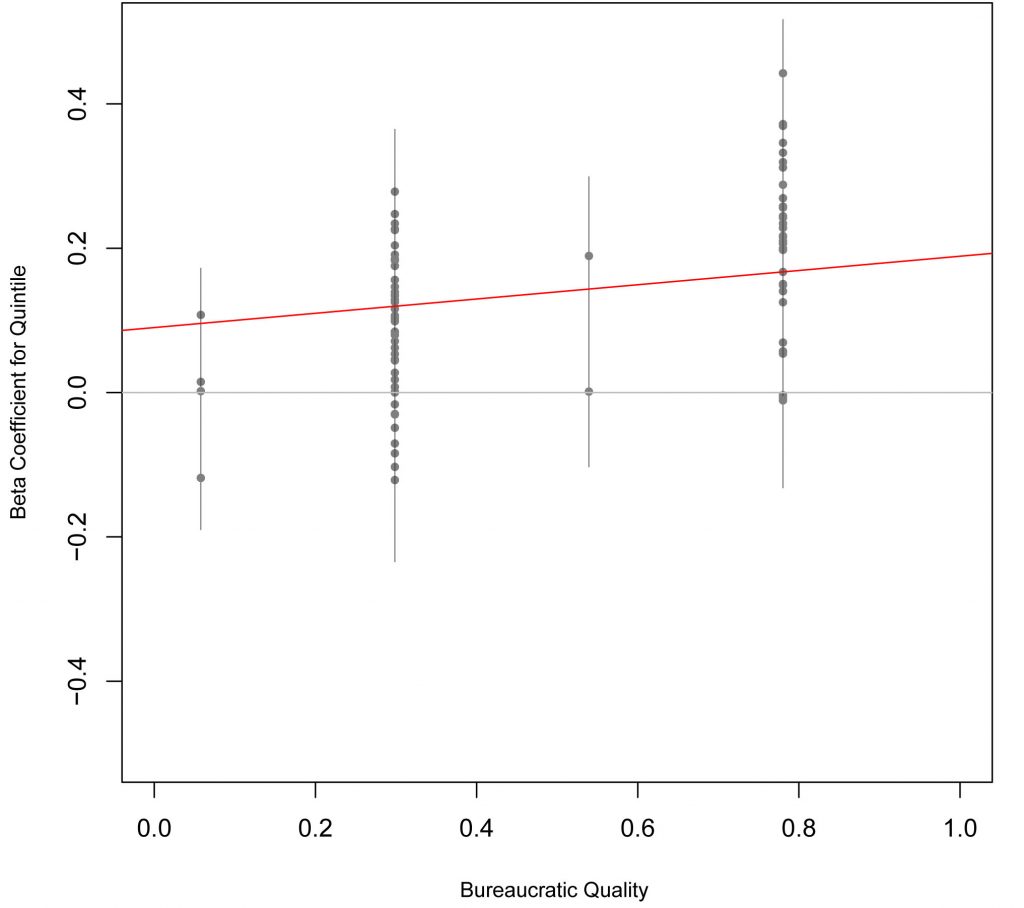

We measure the potential tax exposure of the rich in two ways. First, we focus on whether redistribution from the rich to the poor is a politically salient issue. To do this, we show that that when the stated partisan preferences of the rich and poor diverge – where voting is more polarized by income – relatively wealthy people vote at higher rates. Second, we show that when a state’s fiscal capacity is higher – measured using several variables including bureaucratic capacity and direct tax collections – relatively wealthy people vote at higher rates. For each country and survey-year we regress a dummy for participation on income quintiles while controlling for age, gender, urban residence, and secondary education. The figure below plots the regression coefficients of the income quintile variable for these logistic regressions against our measures of Voting Polarization and the Bureaucratic Quality of the state.

Figure 2: The Estimated Effect of Income

As a result of the conventional wisdom that SES and voting are negatively correlated, researchers often treat higher turnout as an indication of the increased mobilization and political effectiveness of the poor. Experimental studies in developing countries, for example, frequently use turnout to measure the political participation by newly empowered and informed voters (See Pande 2011). Similarly, research reconciling economic inequality with low rates of redistribution uses turnout rates as a proxy for the political mobilization of the poor. Our research suggests that the interpretation of political significance of increased turnout depends upon whether it takes place in a context where the wealthy turn out to vote at higher rates than the poor.

Kimuli Kasarais an associate professor of Political Science at Columbia University. She studies ethnic demography, political violence, and distributive politics.

Pavithra Suryanarayan is an assistant professor of international political economy at the School of Advanced International Studies at Johns Hopkins University. She studies fiscal capacity, group-based inequality, and voting behavior in India and elsewhere.